Chief Justice Of NH’s Highest Court – Jeremiah Smith’s Decisions

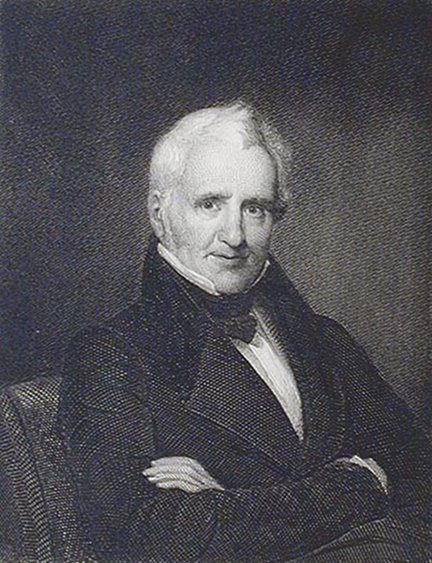

PHOTO: Judge Jeremiah Smith

by Robert Hanaford Smith, Sr.

Weirs Times Contributing Writer

Settled law of the State of New Hampshire.

Believe it or not, until the early 1800’s the settled law was that towns could tax their citizens to pay the salaries of the settled ministers of the established church in the Granite State. The established church was recognized as the Congregational church. The United States constitution added the First Amendment with the much repeated “ establishment clause ” which states that the Congress cannot pass any legislation that establishes any religion or prevents the free exercise of religion. But the state constitutions allowed established religions and many of them, including New Hampshire, had established churches which benefited from taxation.

After Jeremiah Smith was appointed the Chief Justice of the Supreme Judicial Court of New Hampshire things changed. A case was brought before the Court called Muzzey versus the Assessors of Amherst, N.H.

In 1802 a similar case had come before Judges Farrar and Livermore in which Universalists objected to being taxed to the benefit of the Congregationalists. The judges affirmed a previous court decision that Universalists were of the same “persuasion, sect, or denomination” as Congregationalists and could thus be taxed to support settled ministers of the “Orthodox Church.”

When the Muzzey versus Amherst case came before the court led by Justice Smith a different conclusion was reached. This time it was the Presbyterians who didn’t want to be taxed to support the Congregationalists. Jeremiah Smith, though a Unitarian, was also Scottish, and he and all but one of the other Supreme Judicial Court Justices of New Hampshire ruled that Presbyterians and Congregationalists were not the same religious sect “within the meaning of the constitution.” Justice Smith kept extensive records of the cases he was the overseer of and his son, also Jeremiah, made them available. Some of the decisions of the court were printed in the March, 1879 issue of the Granite Monthly.

The decision of the highest court in New Hampshire appears not to have been hailed as a victory for the separation of church and state, but as “the pioneer decision here in favor of religious toleration.” “Here” being New Hampshire. It declared that the Presbyterian Church was independent from the established church and could function as such.

Chief Justice Smith is credited with being “the pioneer in the field of jurisprudence in New England,” and “the greatest master of probate law in New England.” Daniel Webster, with whom he worked as a lawyer, is said to have benefited from the manuscripts that Smith produced.

The Granite Monthly article of 1879 explained why “The statute law when Judge Smith came to the bench was in a crude, chaotic, and unsatisfactory condition, and the common law, worse.”

As late as 1660 New Hampshire was considered, under the oversight of proprietors, to be governed by England. Dover, Portsmouth, Exeter, and Hampton, our first English settlements “…did substantially as they pleased ” until coming under the jurisdiction of Massachusetts.

The first set of laws brought forth by the province in 1679-80, based on the Biblical Mosaic law, was rejected by the “Privy Council” in England. Remember that as long as we were a province we were under the control of the mother country. No laws for the province of New Hampshire were published until 1716 and there was no printing press here until 1756. When Justice Smith took charge of the judges, we are told, that with some exceptions, “the bench was filled with broken-down ministers, lumbermen, bankrupt traders, and cheap lawyers.”

One of the cases that Smith’s court decided involved a situation that reminded me of a similar one encountered during my childhood.

One summer day our neighbor’s children informed us that they had found a patch of raspberries on our property at a spot in the woods where lumbering had taken place. Some time afterwards we went to that place with our berry baskets to pick some raspberries. When we arrived we found our neighbors already there helping themselves to the berries. So the question was, “who has a right to pick the berries? Is it “finders keepers, losers weepers?” or do they belong exclusively to the owners on whose land they grew? In this case, regardless of what the legal direction might be it was “first come, first served.” Both families, however, were able to enjoy some of the raspberries.

In the court case decided by the Smith court in the early 1800’s, the question concerned the ownership of a bee hive found in a tree in the woods. Fisher versus Steward involved some folk in Claremont. One of the persons involved found a swarm of bees in a tree on another person’s land. He somehow marked the tree so he could find it again and went and told the owner what he had found. I should add that with the bees was the honey they had produced. The question was, “Did the honey belonged to the man who found the hive of bees?” The ruling of the court was that the man who discovered the bee hive on another man’s property, and notified him of his find, does not have a right to the honey.

Morey versus Orford Bridge involved what was described as “the constitutional question as to whether a grant of a ferry and the like is a contract which the constitution of the United States prohibits the states from impairing.” Simplified, I think the question involved whether granting a ferry to transport people across a body of water prohibited any other means of getting people (or things) across the same.

This involved establishing a monopoly for transportation at a particular site and denying any competitive means of crossing the water. Judge Smith held that “a ferry and a bridge, though they serve the same end, are things solely distinct in their nature; that the grant of a ferry does not prohibit persons from crossing or enabling others to cross in any other way…”

Jeremiah Smith had an impressive resume. He was born in Peterborough, New Hampshire in 1759, only a decade or so after the first settlers arrived there and built their log houses. He died in Dover in September of 1842 and was buried in the Winter Street Cemetery in Exeter, N.H.

There is much more to be said about him, including that he was the sixth Governor of New Hampshire.

Robert Hanaford Smith, Sr., welcomes your comments at danahillsmiths@yahoo.com