Raging Rivers Flooded New Hampshire WPA Rushes In To Repair 1936 Damage

by Robert Hanaford Smith, Sr.

Weirs Times Contributing Writer

According to William P. Fahey, the New Hampshire Administrator for the WPA , “The floods in 1936 caused the greatest damage in New Hampshire’s history.” The floods came in the month of March and were caused by a combination of warm winter weather causing snow and ice to melt and heavy rain falls of between four to eight inches from March nine to thirteen, and another four to ten inches between March sixteen to nineteen. The rain fell throughout the state with the amounts varying from place to place.

By the 12th of March people were concerned about what was to come because the rivers were experiencing rising waters as the rain fell and ice that still covered them began to break up causing huge chunks to begin moving downstream.

By the 19th of the month the rivers and smaller streams, as well as the lakes were overflowing and there was serious flooding throughout the state. The October 1936 WPA report called Raging Rivers described the situation as follows: “Not a single main highway in any section of the State was open. Not a single railroad train moved from Nashua to Canada. Parts of the State resembled a lake and only the Ark and Noah himself were lacking. Motor boats, canoes, flat-bottomed boats and rafts were pressed into service everywhere. Hundreds of families were rendered homeless. Most of the mills and factories were closed. Bridges both modern and old were going out or were being weighed down with sand-bags and iron to save them. Gas, telephone, and electric service were cut off. Sections were isolated and frantic relatives waited in desperation to hear from their loved ones in cities and country towns.”

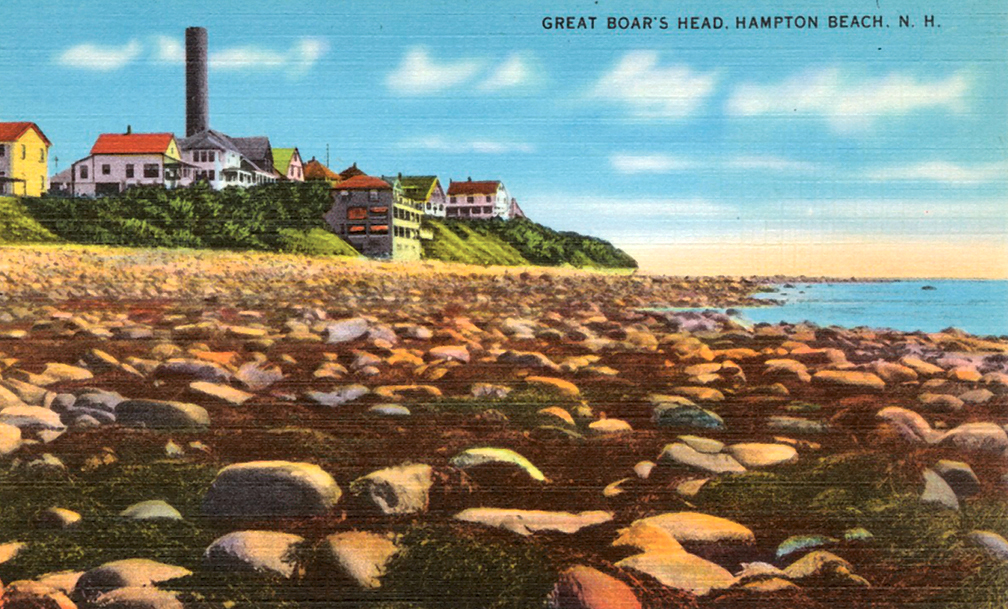

Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones Collection.

Today WPA to some means Wi-Fi Protected Access, but from 1935 to 1943 it was the initials of the Works Progress Administration. The WPA was a government program which was part of President Roosevelt’s New Deal during the Great Depression. Many of the projects undertaken by the WPA involved work on the infrastructure of the country. Much of the work was done by unskilled workers.

When the flood waters threatened destruction in the State of New Hampshire in 1936, WPA engineers and workers were immediately called upon to help and they worked during the flood in an effort to minimize the damage and after the flood to restore damaged areas. Much of the State was affected by the devastation with Nashua having said to suffer the greatest flood damage in its history with 2300 homeless people and a million dollars of industrial loss. Concord was said to have been completely isolated for three days and three nights.

In the central part of the State Franklin was reported to have been hit the hardest by the flooding. The overflowing waters from the Winnipesaukee River covered Central Street to a depth of four feet.

The north country wasn’t spared as Coos County experienced the highest flood waters on record. The Androscoggin and Ammonoosuc Rivers overflowed. The large rivers like the Connecticut, Merrimack, and Pemigewasset were assisted by smaller rivers like the Baker, Contoocook, Sugar, Mascoma, and Ashuelot in causing destruction throughout the State. In Plymouth, passengers on the Montreal Express train, which was stranded a mile south of the railroad station, were taken in rowboats to safety at a hotel. The Smith Bridge road was washed out and the residents in homes in the flooded Intervale in Holderness escaped by boat into Plymouth. Three major bridges were destroyed in Manchester and others over streams throughout the State were damaged or lost. Some structures that were in danger of being destroyed by the raging waters were saved through the efforts of workmen sent out to limit the damage by the use of sandbags,etc.

The report of the WPA indicated that by March 18th it had been “placed at the disposal of the State.” Other agencies also contributed to relief efforts, including the Red Cross, the Salvation Army, and Legion Posts. Besides the men working under the WPA there were women WPA workers involved in the relief work, 413 of whom were given assignments to aid the Red Cross. After the flood waters subsided the work of WPA crews continued with “mopping up” projects and repairing damaged property, particularly roads and bridges. Eight hundred men were assigned to the Manchester area to remove sand and silt and other debris from the streets, etc. Six hundred more were given the task of solely cleaning out catch basins so they could take care of the water which had to be pumped out of basements.

WPA workers were assigned to work in towns throughout the State in response to the requests received from town officials, mainly the selectmen.

On September 15, 1936, the work in some towns had been completed, but there were still 2,772 WPA workers on flood repair damage in 132 New Hampshire cities and towns. In the Lakes Region, for example, Laconia had 14 workers, Belmont had 8, Meredith had 12, New Hampton had 27, Holderness had 22 as did Plymouth, Bristol had 32, Alton had 25, Barnstead had 20, Center Harbor had 7, and Franklin, the hardest hit in the area, still had 104 WPA workers employed at several projects.

Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones Collection.

On March 25, 1936, then Governor Styles Bridges wrote a thank you note to WPA Administrator William Fahey to express thanks for the agency’s help with flood damage repairs and spoke of the flood reconstruction council that was established by the Governor and Council to oversee and “coordinate all agencies within the State in uniting to carry out a successful program of rehabilitation.”

The 1936 flood damage was estimated to amount to $25 million in 1936 dollars. It should be noted that the work of the WPA involved public property repairs and not privately owned property. This was one of the projects paid for by the government to give jobs to the many unemployed during the Great Depression. The WPA also constructed the Gunstock Mountain Resort (then called the Belknap Recreation Area) which was finished in 1937 and the Attitash Mountain Resort in Bartlett which was finished in 1938.

The agency even provided jobs for writers, one result which was a New Hampshire Guide Book, written by workers of the Federal Writers Project. But I wonder if there are any readers who have recollections of the 1936 flood and the connection to the WPA.