Raising Something For The 4th – The Cost And The Celebration -Part 1

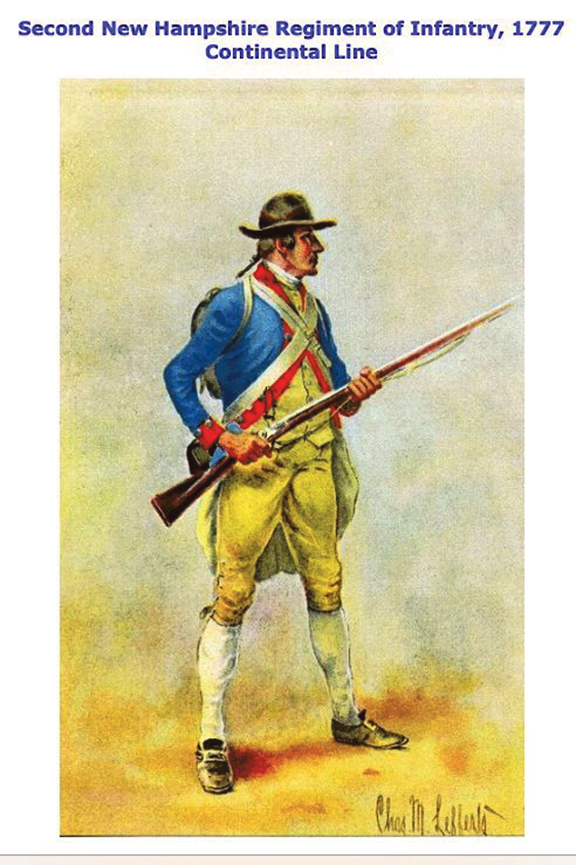

PHOTO: A Solider in The NH Second Regiment – 1777.

by Robert Hanaford Smith, Sr.

Weirs Times Contributing Writer

Seventy-six years after the signing of the Declaration of Independence a couple of boys wanted to find a way to raise something “for the Fourth.”

These two boys had several brass rings which were polished up to have a nice shine, though their worth at that time was probably no more than a penny. Not everyone knew that, however, and the boys thought up a scheme where they would stop people on the street and ask them if they had lost a ring. Some would look at the ring and continue on their way indicating that the ring wasn’t theirs. But others would look at the ring and say, “I believe I did lose one like this.” They then would inquire where the boy found the ring and pretend it was their lost ring. If they didn’t offer to give the boy a reward for “finding their ring” he would ask for one. In this manner the boys were able to “return” several “lost rings” and receive rewards of more pennies than the rings were worth, in this way raising money with which to celebrate the Fourth.

One of the boys reportedly received fifty cents for one of the rings.

It has been 244 years since that famous declaration was signed, yet the yearly celebrations go on, and children, adults, and whole towns still seek ways to raise money to help celebrate the event.

This year with the toned down celebrations provides a good time to remember that Independence came at a cost. In 1775 and periodically through the war the States were raising troops for the War. The armed forces of the American colonists in the Revolutionary War did not come from a standing army, meaning that there was no permanent federal army when the war began in 1775.

This year actually marks the 245th birthday of the United States Army which was formed from militias from the States whose organization began in the towns. Many people in those days were opposed to a standing federal army, fearing that such would be a threat to the freedom individual states had to govern their own affairs.

In 1775 the State of New Hampshire had twelve Regiments which were made up of companies of volunteers from the various towns. Regiments were made up of from 200 to 750 men and the number was increased to 18 Regiments in 1777. All male residents in the state were divided into two classes for service in the militias. The active list included those between the ages of sixteen and fifty, and the alarm list included all those between the ages of sixteen and sixty-five who weren’t on the active list.

Certain classes of people in official positions were exempted from the militias. Those on the active list were supposed to attend sessions for drills and instructions eight times a year and those on the alarm list two times a year. My reading about these drills indicates that the guidelines were not always followed and not taken that seriously and became more like gatherings for picnics and fun than for serious military training.

We can only imagine what it was like for those men who responded to the alarm of April 19th sounded by the events at Lexington, Massachusetts, by immediately leaving their homes and some in two hours time gathering in their towns and heading south on foot or on horseback ready to take part in the beginning battles of the Revolutionary War.

In May of 1775 the Fourth Provincial Congress of New Hampshire officially placed their support behind the cause of resisting the British forces by voting to raise two thousand men to serve in three Regiments. The men were volunteers and they had to furnish their own arms and equipment. They were paid thirty shillings a month, were given a travel allowance of a penny a mile, and allowed four dollars for an over-coat.

Because enlistments were for short periods of time and all calls to active service had to be approved by the State Legislature there were numerous calls to raise more men.

On September first of 1775 the Fourth Provincial Congress voted to raise four regiments of Minute Men out of the militia to be ready for immediate duty. They were to serve for four months and then keep re-enlisting for four additional months as long as needed. Another call came from Generals Washington and Sullivan on the first of December in 1775 to New Hampshire and Massachusetts to raise five thousand men to replace the men of the Connecticut militia who had been offended by something and, instead of continuing their service, returned home. New Hampshire provided 1800 of the replacements and Massachusetts provided the remainder. New Hampshire also raised three companies to serve in Canada.

There were no Revolutionary battles fought in the State of New Hampshire, partially because their militia men, especially General Stark, worked diligently to keep the enemy forces out of the State by defeating them in places like Canada, New York, Rhode Island and Massachusetts. The Legislature would raise men to guard particular sites within the State with companies regularly being assigned to guard the coast. Ships for the Navy assembled during the war were built in and launched from Portsmouth.

An article by Judge Jonathan Smith in a Granite Monthly magazine indicated that the year 1776 was an especially busy one for raising colonial troops and that the signing of the Declaration of Independence gave the militia men new incentive to fight for freedom. Each new vote of the Legislature to raise troops involved a new pay policy. The vote in January to raise two regiments of 780 men each to serve for two months came with the promise of advance pay for those two months. The vote in March of 1776 was to raise a regiment of 725 besides 300 additional men to serve as guards at the seacoast for nine months, and for 760 men to serve in the Continental army in Canada. In July the vote was to send another 750 men to Canada to serve until December. Those men were offered a bounty of seven pounds for equipment and one month’s pay in advance while their regular pay remained the same. In August another one thousand men were raised in response to a call from General Washington to serve in New York. They also received advance pay and a bounty of six pounds.

More help was needed for General Schuyler in New York and a draft, rather than the usual volunteer procedure, was used in December, 1776, to raise 500 men out of the militia to serve in northern New York State.

They were to serve until the following March for three pounds a month.

I have used the word “raised” multiple times to draw a contrast between the raising of soldiers to fight a war and the raising of money down through the years to celebrate the freedoms they won when they won the war.